U.S. War Crimes in Iraq for Israel

Statehood For Peace and Freedom

9/8/20258 min read

Before the launch of the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad provided its American counterpart, the CIA, with lists containing the names, addresses, and phone numbers of Iraqi nuclear scientists.

These brilliant scientists had been working at the Osirak nuclear reactor, which Israel bombed on June 7, 1981.

Most of them survived that Israeli airstrike, and the former Iraqi regime took care of them, assigning them to Iraqi universities to further develop their expertise in nuclear physics.

Indeed, the lists of these Iraqi scientists were distributed to U.S. Marines stationed at American military bases in the Gulf.

The orders from U.S. command were clear: these scientists would be the first targets after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime.

The Marines were instructed to storm the homes of these scientists, abduct them by force and transfer them to America — or kill them if necessary.

And this is exactly what happened.

The operation to eliminate Iraqi minds began on the second day of Baghdad’s fall, when U.S. military units spread out to hunt down scientists, researchers, intellectuals, and doctors — especially those in the nuclear and chemical fields.

At the top of the list was Dr. Huda Salih Mahdi Ammash, nicknamed “Mrs. Anthrax” by U.S. forces.

She was a brilliant Iraqi scientist, head of the Iraqi Microbiology Society at the University of Baghdad, holder of a PhD in microbiology, with extensive research in chemical radiation and biological weapons.

She was arrested by U.S. forces on May 9, 2003, in Baghdad, just weeks after the American invasion.

She was one of the two most wanted Iraqi women scientists by U.S. forces, the other being biological scientist Rihab Taha, who was also arrested.

In the end, U.S. forces managed to gather more than 70 Iraqi nuclear physicists, abducting and transporting them to Florida in the United States.

Those who refused to cooperate with America were immediately killed in their homes.

The total reached 310 Iraqi nuclear scientists.

The aim of the West and Israel was to eliminate these Arab minds, which they considered more important than any other target.

As former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright once declared: “What can we do with Iraq other than destroy its minds, which atomic bombs cannot destroy? Destroying Iraqi minds is more important than dropping bombs.”

Source: Dr. Abdullah Al-Nafisi, Al-Mushahid Al-Siyasi Magazine (UK).

Dr. Huda Salih Mahdi Ammash received her undergraduate degree from the University of Baghdad, followed by a master's in microbiology from Texas Woman's University in Denton, Texas.

She spent four years at the University of Missouri pursuing a doctorate in microbiology, which she received in December 1983.

Her thesis focused on the effects of radiation, paraquat and the chemotherapy drug Adriamycin, on bacteria and mammals.

She was appointed to the Revolutionary Command Council in May 2001.

In one of several videos that Saddam released during the war, Ammash was the only woman among about a half-dozen men seated around a table.

The videos were broadcast on Iraqi TV as invading forces drew closer to Baghdad: it is not known when the meeting took place or what the significance was of her appearance on camera.

She served as president of Iraq's microbiology society and as dean at the University of Baghdad.

U.S. officials said she was trained by Nassir al-Hindawi, described by United Nations inspectors as the "father of Iraq's biological weapons program."

She conducted research into illnesses that may have been caused by depleted uranium from shells used in the 1991 Gulf War and had published several papers on the health effects of the war and the subsequent sanctions.

NEWSWEEK 2005

Shortly before the Iraq war began in March 2003, I didn't believe Huda Salih Mahdi Ammash when she insisted, in an interview, that Saddam Hussein's regime was not developing biological weapons.

Dubbed by Washington "Mrs. Anthrax" or "Chemical Sally," Ammash was then Iraq's most powerful woman.

She'd been accused by U.S. investigators of heading a program, into the mid-'90s, that involved the attempted weaponization of anthrax, smallpox and botulin toxin.

On Monday, her Baghdad lawyer confirmed that Ammash was one of around two dozen Saddam-era officials released from jail without charges.

A U.S. military spokesman in Baghdad confirmed a number of so-called "high-value detainees" had been released because "they were not considered to be a security threat, and they were not wanted on charges under Iraqi law. So we no longer had any reason to continue detaining them."

Ammash and another woman, Dr. Rihab Rashid Taha, a British-educated biological-weapons expert that American officials called "Dr. Germ," were among Saddam's most notorious scientists.

They were believed to have run the Baathist regime's biological-weapons programs.

When Ammash was detained in early May 2003, I simply assumed she would go on trial for war crimes as one of the masterminds of a WMD program that was, after all, the reason why the U.S. and British governments had insisted on regime change in Baghdad.

When I interviewed Ammash, it was early March 2003 and Saddam was still in power.

Ammash was tastefully dressed in Western clothes and jewelry--in contrast with the stern, headscarved image that later appeared as the Five of Hearts among the U.S.-issued deck of cards showing the 55 regime officials "most wanted" by the American-led Coalition.

Ammash was the only woman in the deck, reflecting the fact that she was the only female on the ruling Revolutionary Command Council, Iraq's top decision-making body.

During the interview, she declared: "To end one's career in defense of Iraq is an honor."

Ammash laughed while recounting the anonymous phone calls that were bombarding her and other Saddam aides, urging them to defect and abandon the regime for the sake of their families.

She said she'd received e-mails filled with computer viruses, as many as 18 in a single day.

"It doesn't fit the image of the U.S.," she complained, evoking the notion that gentlemen don't mess with a lady's e-mail.

Articulate and well-mannered, Ammash had been educated in the United States; she received a masters from Texas Woman's University in Denton and a doctorate in microbiology from the University of Missouri.

She was said to have been a key figure in Saddam's biotech and genetic research programs and to have been trained by Nassir al-Hindawi, the alleged father of Iraq's biological weapons efforts.

However Ammash told me her scientific work focused on the what she called the carcinogenic effects of depleted uranium, which had been present in some U.S. bombs and missiles during the 1991 war to liberate Kuwait from Iraqi occupation.

Of course, I didn't believe everything she said (and she probably didn't believe I was a journalist acting in good faith, either).

Although we talked for nearly two and a half hours over tea, this was hardly a normal interview.

It was a chat on the eve of war.

Ammash and I both knew that bombs would soon be falling on Baghdad and that Saddam's regime was, most likely, in its last days.

One thing Ammash said did stick in my memory.

She stressed that Iraqis remained fiercely proud of their civilization despite decades of violence and deprivation.

"This country is Mesopotamia. Ninety-nine percent of the American people don't know the country they'll soon be bombing is Mesopotamia," she said. "This nation has been serving civilization for 6,000 years. We invented the first alphabet...every American who enjoys education owes that to us."

To be sure, the "Mesopotamia card" was part of a spiel that Saddam's aides had propagated before the war in an effort to stir up international sympathies.

But pride in their history is also one reason why even Iraqis who opposed Saddam remain so resentful of what they see as foreign occupation.

When I was in Iraq on assignment for a couple of months this past summer, some Baghdad friends who'd welcomed the sight of American Marines in 2003 now nurtured a festering and deep-seated ambivalence about the U.S.-led occupation.

Some said they actually preferred the yoke of an Iraqi autocrat such as Saddam to the rule of an American conqueror, even a benign one.

Today it's obvious that many aspects of the U.S. presence in Iraq have been far from benign.

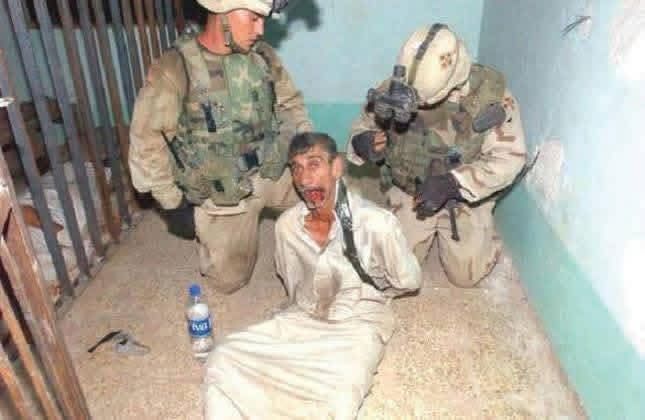

When Ammash's husband, Ahmed Makki Mohammed Saeed, told me in 2004 that he'd been "tortured" while being detained by U.S. authorities, I wasn't sure whether to believe him.

Revelations about U.S. abuses at Abu Ghraib prison had not yet surfaced.

And his accounts sounded bizarre: being subjected to hours and hours of earsplitting American rap music laced with profanity and being doused with cold water, then forced to stand for hours in front of a freezing air-conditioner turned up full blast.

Still, the sheer weight of detail suggested to me that he wasn't making it up.

And subsequent tales of torture from other former detainees indicated that he might actually have been one of the luckier ones among them.

The Saddam-era officials who are now suddenly free will undoubtedly have their own stories to tell--assuming they feel safe enough to talk.

(Some officials in the current Shiite-dominated government have already vowed to track them down.)

Ammash's husband earlier claimed that she had changed dramatically during detention.

A petite woman to begin with, she'd lost nearly 20 pounds, and her once jet-black hair had turned white "nearly overnight," he said.

Her lawyer had argued for leniency on medical grounds because he said her detention brought on a recurrence of breast cancer.

A number of those freed were reported to have been flown out of Iraq aboard U.S. military aircraft out of concern that their lives are in danger.

In addition to Ammash and Taha, the detainees released include former education minister Humam Abd al-Khaliq, whom United Nations weapons inspectors accused of trying to coverup Iraq's nuclear weapons program before the 1991 war; Hossam Mohammed Amin, who'd headed the weapons inspections directorate, and Aseel Tabra, a former Iraqi Olympic Committee official and secretary to Saddam's late son Uday.

Why now? In the wake of Iraq's elections, U.S. officials hope to indicate to hard-line Sunnis and some former Saddam loyalists that they too have a stake in the new Iraq.

Sunni insurgents often have demanded prisoner releases as a condition for ending their violent rebellion.

A particularly ruthless group of Sunni kidnappers specifically demanded that Iraqi women detainees--Ammash and Taha key among them--be freed last year after Briton Kenneth Bigley was taken hostage.

He was killed in September 2004 after the kidnappers' deadline passed.

It'll take more than a few prisoner releases to convince Sunni insurgents to lay down their arms.

On Monday, an extremist group calling itself the Islamic Army of Iraq posted video on a Web site purporting to show a man being shot in the back of the head.

It was impossible to identify the victim, though the video also showed an identity card belonging to American contractor Ronald Allen Schulz.

Eleven days earlier, the group had claimed to have killed Shultz.

The timing of the gestures of leniency also came just a few days after President George W. Bush conceded that 2003 intelligence reports on Iraq's purported WMD programs were flawed.

Now we're being told by media quoting a former Western arms inspector, that Ammash was cooperative in detention and provided U.S. interrogators with credible evidence that Saddam did not have an active WMD program before the U.S.-led invasion in 2003.

When Saddam was still in power, most of us journalists reporting in Iraq simply assumed it was impossible to get a straight story out of his officials.

Now we know Saddam's aides weren't the only ones spinning the truth.

It's hard to know what to believe any more.

Statehood for Peace and Freedom

Exploring pathways to lasting Middle East peace.

contact@statehoodforpeace.com

© 2026. StatehoodForPeace.Com - All rights reserved.